Romance Comes for Mr. Death

A lady reporter doesn't kiss and tell. A lady reporter kisses and publishes.

I didn’t see a dead person until I was twenty-five, which might explain a thing I once had with a French forensic pathologist who worked at the New York City Morgue. Not at the morgue, my love life was not so Bret Easton Ellis, but within commuting distance, and with that mystery which is death hovering about us like some dizzying and exotic perfume, though that may have been the formaldehyde.

Maybe, now that I think about it, I was twenty-eight or twenty-nine when I saw my first body. I was a reporter, sent out to cover a jumper, in Brooklyn Heights. “Decided to take flying lessons”, was the way the editors referred to this type of story, with “Jumped or pushed?” the critical question to resolve.

The critical thing for me, heading over there, was not to embarrass myself by throwing up. That wasn’t as hard as I suspected, as this was not a splattering fall; the man who had killed himself (no mystery, he’s left a note) had jumped from his sixth-floor apartment, and the part of his face I saw was perfectly intact, although a pool of blood was slowly spreading out from behind his head.

“I handled that pretty well, that didn’t bother me at all,” I thought, heading back to the office, though in the middle of the night, the image of that widening pool of blood kept repeating in my mind like a tape loop and I couldn’t shut it off.

(Excuse me, I’m receiving telepathic feedback from a reader in Duluth:

What the hell? I thought this was going to be about fucking. I am so out of here—

Damn. And I was so hoping to finally get my reader numbers up to 3,000.)

Where was I? The eroticism of death; newspapering in the lascivious ‘70s when me and my friends were in our lascivious 20’s…Oh, right, the New York City morgue.

The paper I work for is The New York Post, then a lefty tabloid. It is also where I meet my friend Herb. We are both feature writers, which means we are particularly fascinated by weird stuff and one day another reporter, David Rosenthal, who would go on to a much more respectable career, tells us about a museum at the New York City morgue. It’s closed to the general public and it’s about the bizzare ways people have been killed in New York City – foul play, medical negligence, the occasional barbell falling from great heights on the random, unfortunate head. They also have an exhibit so lurid that it is kept in a locked room, that you only get to see if you know it’s there and you ask.

Herb and I are generally not museum people, but honestly, isn’t this why people move to New York, for the experiences you can find nowhere else?

We arrange for a late Saturday morning visit. The morgue is a dark, gloomy building at First Avenue and 30th Street. You can imagine the architect saying, “Hey, people are going to be coming to identify loved ones killed in airport bombings – it should be depressing. I say we put fluorescent lighting in the waiting room, use a sickly green paint throughout – can someone bring me the municipal paint chips? -- and, I’m on fire! -- put a crack in the viewing window where they bring up the bodies for the families to ID, to be sure we hit the right note.”

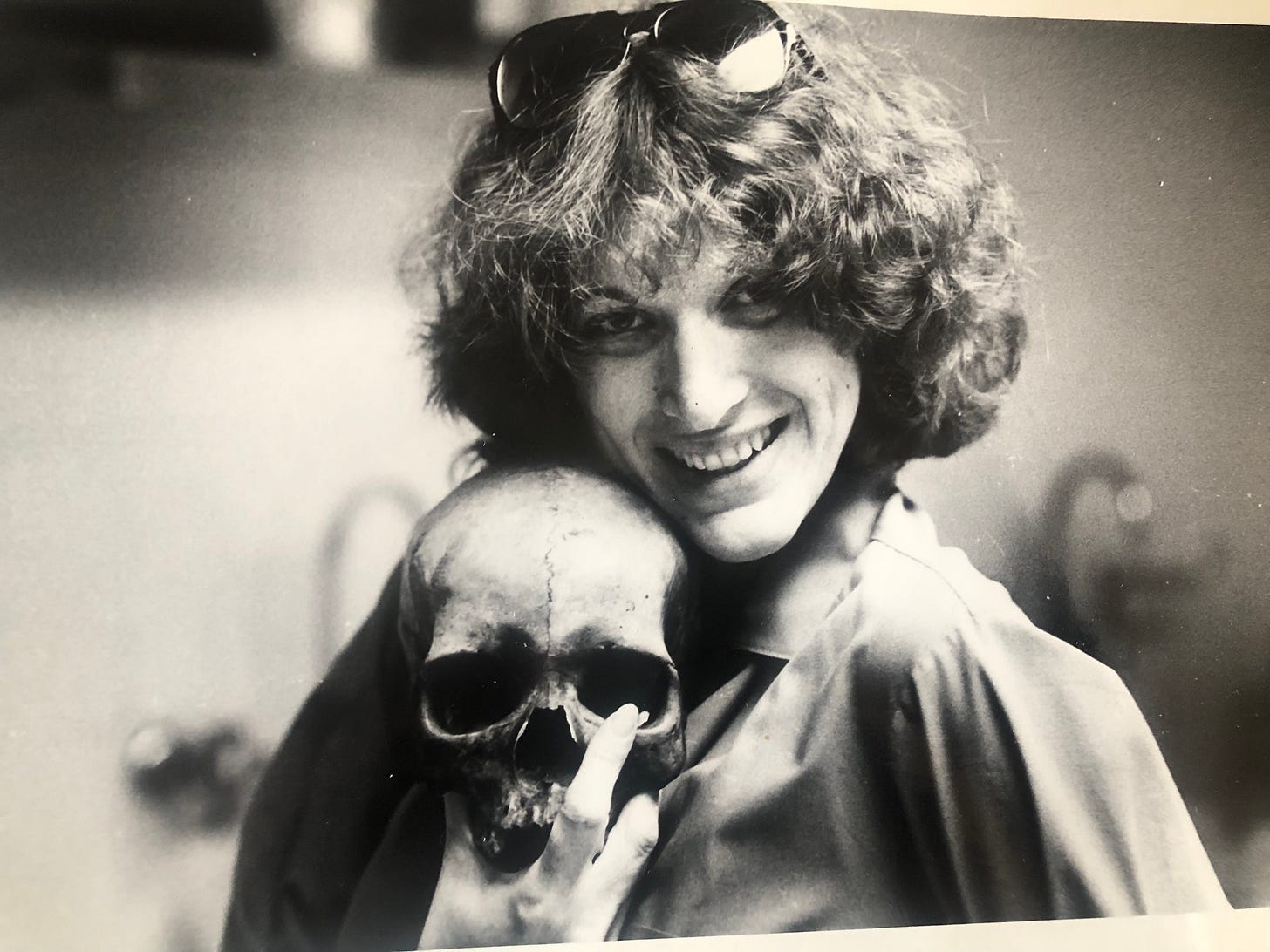

Our host for this outing is Jean-Pierre Lahary, a Frenchman who is the chief forensic technologist at the Medical Examiner's office. Lahary’s specialty is identifying bodies that have been damaged beyond visual identification – air crash victims; the aromatic and bloated floaters that pop up to the surface of the Hudson with the spring thaw; victims of mob hits in which people you used to have espresso with decide to remove your head and hands, to hamper ID. In such surroundings, would anyone notice that the French forensic technologist is hot? You bet. M. Lahary, with his dark hair and short, muscular body, is exactly my type, but today Herb and I are here for more elevated pursuits, to tour a one-of-a-kind museum, and M. Lahary is sort of our death docent.

What are the highlights of this museum that remain with me these forty-five years later?

A small airplane window, imprinted with the outline of someone’s head, when the Lockheed Electra in which he was traveling crashed into the East River on a descent into LaGuardia.

A unknown man’s head floating in a jar of formaldehyde, grey and forlorn. (Beauty Note, which I hope my Substack colleague Jessica DeFino, whose work I much admire, investigates: Why is it that no one looks good pickled? You see a head merely tossed into a jar with generic tissue fixative, you realize what effort must have gone into the upkeep of Stalin and Evita, though at least she got a few good tunes out of it.)

A dumbbell, which a cleaning lady had been using to prop up the Park Avenue window of ‘60s talk show personality Arlene Francis, which toppled out and fell on the head of an unfortunate out-of-towner who had come to New York to celebrate his birthday.

This wasn’t, by the way, a slick operation like you see at MOMA. There was a quirky, but much-loved vibe about this museum which you often see in amateur undertakings; hand-lettered signs on cardboard, with strings leading to the featured body parts. In the rather extensive medical mishaps display, for instance, you saw the female reproductive organ, punctured by a sharp object, with its respective strings and signs: “Uterus”. “Swizzle stick.”

(Excuse me, I have an urgent IM from a reader:

What was the provenance of that uterus?

Sorry, no idea. New York was full of crummy apartments in the ‘70s, so it was possible to find a back-street abortion that could kill you anywhere. Now things are so expensive I doubt you could even get one in Queens. And the museum was dismantled years ago, after a spoil-sport story in The New York Times, making a big deal out of the head.)

But you are, no doubt, eager to hear of the smutty exhibit in the mystery room, which Herb and I had to figure out how to get into without seeming prurient. There was much whispered arguing about this one. “You do it!” “No, you!”, but being the more out-going member of the pair, the task naturally fell on me.

“So, I hear that you have a very, uh, special exhibit,” I say to Mr. Lahary, in my most refined manner, which is kind of hilarious considering the way things would work out between us.

Does Monsieur Lahary leer? Does he mistake Herb and I for a couple who are planning to get a room directly after the viewing? Does he envision me naked? My God, I hope so.

Anyway, M. Lahary gets out the keys and opens the room to the sanctum sanctorum. Maybe I should call it the pervo sanctorum. Lahary is smirking all right. And who would not? For before us stands a large bicycle, the seat of which has been replaced by a dildo. An open jar of Vaseline and a pornographic magazine are on the floor beside it.

A man checked into a mid-town hotel room, Lahary says, and in the course of using the custom equipment, punctured his intestine and died. The cops kindly lied to the fellow’s wife about the circumstances of death, saying he had had a heart attack. (“And boy,” I’m thinking, “Would I have loved to have heard the conversation when they got back to the precinct house.”) The museum, Lahary says with some pride, recreated the scene exactly as it was found.

Anyway, that’s that. Herb and I go off to lunch (vegetarian). Mr. Lahary is lost to the mists of a rotating cast of Greenwich Village players.

A year or two later, I get a new job, at The Daily News Magazine. Trolling for stories, I remember Lahary.

How to do justice to our heady first days together? The moment when Lahary walked me through the innards of the darkened, refrigerated morgue, with a flashlight. The time, which I shall always remember, when I ask Lahary to explain exactly what he does and he opens a drawer in the morgue and pulls out the body of a headless, legless man with one arm, minus the wrist. He lifts the deceased onto a gurney (How his muscles ripple under that clinging green hospital shirt!), wheels him into a small room with a blackboard, and explains, as if he were giving a lecture.

“I get this,” he says, gesturing to the body. “And one hour later, I have this” – and here he writes on the blackboard – “ Height: 5’10, Age, 63-65, Weight: 179, Race, Caucasian. The way he determines this, he explains – oh excuse me, there’s another I.M.

“Joyce, I’ve got to pick up my grandchildren. Does anyone get laid in this story or not?

You see what I have to deal with? As Sondheim wrote, and Bernadette sang, art isn’t easy. And neither is romance. I am definitely in lust with this hot little Frenchman, I am itching to sink my teeth into whatever part of his anatomy I can get to first, although I am aware that some of this has to do with his profession.

“I think it has something to do with his proximity to death,” I tell Herb. “It’s like he’s Death’s Handmaiden. What would you call Death’s Handmaiden when he’s a guy?”

“Death’s gofer?” Herb suggests.

But lust and journalism do not mix. I interview Lahary at his home, he shows me his private collection of particularly gruesome murder photos, and makes me dinner.

“Only a Frenchman knows how to make an omelet,” Lahary says and I know he is not talking about cracking eggs.

But I do not make a move. That’s because, regardless of what you see in the movies, reporters cannot have love affairs with the people they cover. After the story is published and you’re off the beat, you’re clear. Or, as Abe Rosenthal, the late editor of The New York Times famously said, “I don’t care if my reporters fuck elephants, as long as they don’t cover the circus.”

I write my Magician of The Morgue story as fast as I can, file and, as I’ve picked up reciprocal vibes from M. Lahary, start planning what I’ll wear when we both get lucky.

Then comes the 1978 New York City newspaper strike. Eighty-eight days of deferred passion and fevered fantasies. If I’d written them down, I’d be writing this dispatch from a country house.

But finally, the strike is over. My story runs in the Daily News Magazine, Monsieur Lahary calls to thank me; i.e. have a cover for asking me out. I have no memory of where we go for dinner or what we talk about or the moment when I ask him if he’d like to come up to my charming West Village apartment for what we then called “a drink”.

What I do remember – what I will never forget, and believe me, for decades, I have tried – is the moment Lahary, who indeed has a beautiful body, strips down, revealing leopard print briefs cut like Speedos.

Oh, shit.

And once they’re down to the briefs, there’s no way you can say, “Damn, I just remembered, early day tomorrow.”

Especially when the big reveal is accompanied by the words, “I can go all night.”

“Please,” I think. “Don’t.”

He did, however, make a great omelet.

———————

This definitely makes me see Arlene Francis in a different light.

Cheers to great (sexy even) memories of hot men!! What a great story! Omlets are so much better made by interesting people.