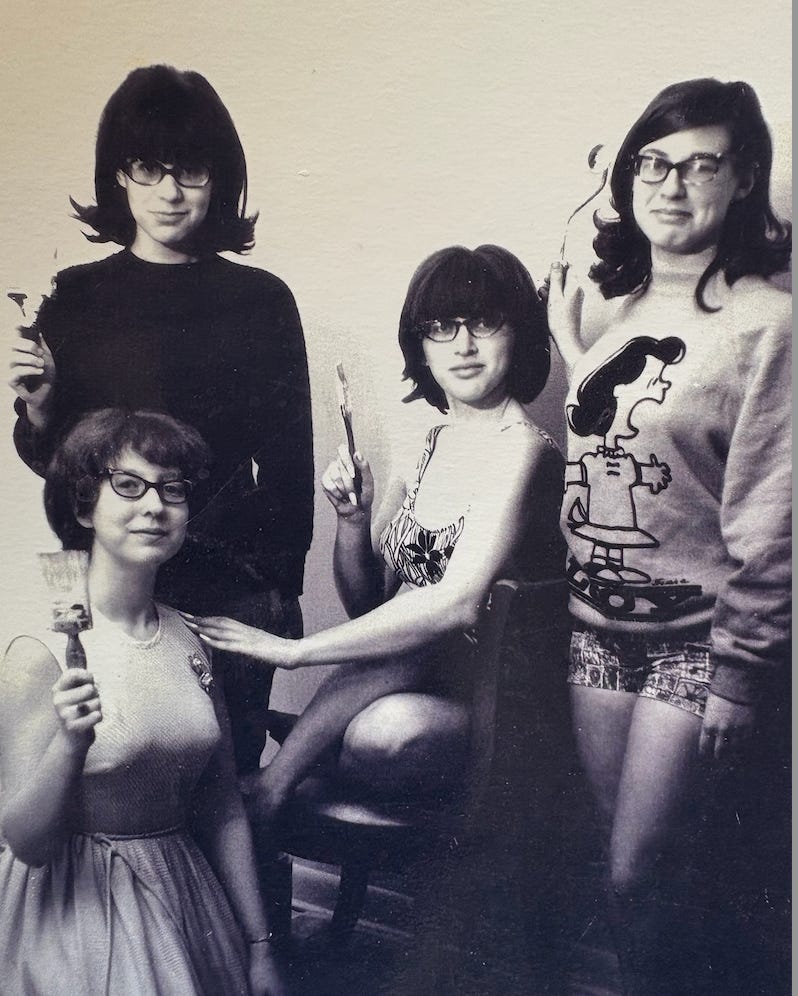

Sue, lower left, Tarner, Joyce and Christy, about to paint an innocent wall purple in the Summer of ‘66

“I know this isn’t the way you would do it,” Sue says when she calls. “You’re an older sister, you want to rush in and fix things, but that’s not what I want to do. I’m 77, I’ve had a great life. I’ll never have a success like I had with the last books. I’ve been lucky. I can’t believe what a good life I’ve had.”

We were four: Me, Christy, Tarner and Sue; NYU, freshman year, 1965. Tarner, who goes by her last name, is the coolest.

“I got bit by a cockroach in the middle of a fuck on Avenue B,” she says.

But cockroaches generally don’t bite people so I must not be remembering that right. Tarner drops out of college, goes to Austin, gets involved in the music scene and kills herself at sixty. The Role of the Second Wife, as prescribed in the Kama Sutra, has not worked out so well, plus there are the rising rents. Then we are three.

“The Unmarriageables,” Sue’s brother has called us in college and he is right because though there are romances, nobody does.

Christy moves to L.A. and becomes a lawyer for poor people. I stay in the Village and become a newspaper reporter. Sue moves to a small city 60 miles north of New York and writes children’s and young adult books. The first, “Just Morgan”, is accepted when she is still in college. The last, “Life As We Knew It”, a dystopian thriller, is accepted after thirty rejections and is a New York Times best seller and kicks off a series.

Sue’s books do not necessarily have happy endings. “The Year Without Michael” is about a teenage boy who goes missing and is never found. “About David” is about a teenage suicide. When it is banned in a middle school in Florida in 1987, I am proud.

“Endometrial cancer, advanced, my doctor says it’s pushing on all the organs,” Sue says. “I told her I’m not doing treatment and she very quickly offered palliative care and hospice. I don’t want to be sick for a year and a half, then spend another year waiting for it to come back.”

Christy flies in from California and we drive up to Sue’s townhouse with a code to let ourselves in.

Sue is in bed, though it is noon.

“I can get up,” she says. “I’m just being lazy.”

Sue is no longer eating and drinks only enough broth to get down pills. Sometimes she uses sherbet. She also tells us that the day before, when she was trying to drink, her throat closed up — that was scary, she says.

Sue had said she did not want overnight guests, but Christy has brought a suitcase anyway. I, less optimistic, have only a week’s worth of meds. But it is obvious that Sue should not be alone, so Christy and I stay. We change the sheets and do laundry and talk for hours. We drink out of Sue’s Dudley Do-Right and Boris and Natasha glasses and serve her broth using the good china with swirling pastels. We watch old movies, a ritual at Sue’s:

“Sing and Like It,” a 1934 ZaSu Pitts comedy with gangsters, which Sue has been saving for us. “Caught,” a melodrama about the perils of marrying for money, which confirms our worldview. Watching old movies, things seem normal except for the night Sue has some chicken soup and goes to the bathroom and retches violently for fifteen minutes. One morning, Sue complains that her belly is getting fat and shows me how swollen it’s become. I know this is ascites, fluid building up, and it will put pressure on the diaphragm and lungs and make it difficult to breathe. The next day, it is even larger.

It’s mid-June. Sue had thought she’d have three to six months, but a week ago the specialist told her three months at most. Now, Sue is doubtful she will make it to July 4th. This impacts our viewing decisions.

“There’s this new series on Netflix the Times says is pretty good,” I say.

“How many episodes?” Sue asks.

I Google it.

“Six,” I say.

Sue laughs.

I search for more detail.

“They dropped them all at once,” I say.

But Sue has canceled her Netflix account, so we watch some old Ed Sullivan shows with Robert Klein and a guy who does hand shadow puppets of JFK and Nixon and The Carpenters with Karen Carpenter on drums. Karen Carpenter’s hair reminds me of us in ’66, sharing a one-bedroom in the Village. It’s a spooky time crunch. Sixty years in between, but they’re compressed; we are our own bookends.

Showering is exhausting for Sue, so Christy and I go to the supermarket and pick up Baby Wipes. We get more chicken broth and sherbet. We find a medical supply store and buy lip moistening swabs, mint and unflavored, which Sue makes fun of but tries for us. One bad night, Sue takes a sleeping pill before she goes to bed and it takes me and Christy an hour and a half to get her up the stairs to her bedroom.

“Do you feel like we’re in one of those old friend dying movies with Bette Midler and any minute somebody’s going to start singing?” I ask Christy the next day.

The rite of giving away stuff had begun the day we arrived.

“There’s a model of the Titanic in my bathroom,” Sue tells me, referring to a small cube, half filled with blue liquid, with a ship and an iceberg you can slosh around. “You once said you liked playing with it. I want you to take it. Look around the house. If there’s anything else you like, I want you to have it. It will make me very happy.”

Sue has written over 75 books. That should give her a shot at a New York Times obit, I think. The third day of our visit, I pull together notes for my pitch. Sue sits on an armchair near a small bookshelf in the den, Christy and I sit on the carpeted floor while I get titles and pub dates from a book on important American children’s and young adult book authors.

“Do you realize how different our lives would have been if we hadn’t gone to NYU and met one another?” Sue says.

I immediately disagree because that’s the way I am.

“Not true,” I say. “You’re a writer, you still would have been a writer.”

“My first book happened because you introduced me to Professor Tebbel,” Sue says. “You said you had this professor who worked in publishing that I should meet. When I couldn’t sell anything and said I was going to stop writing you told me I was a writer and had to keep going and one of my best books came out of that.”

And when I am working on my first novel and struggling with plot, Sue helps me for two years, remembering every character, every detail of the world I am building. She’d discuss a scene with me for hours; do I kill off that character, do I not? Have you made her interesting enough, does she appear often enough, so the reader will care when she dies?, Sue asks and click! , I see what I need and go back and fix it.

On the bookshelf, there’s a framed antique postcard: A vampire, hiding in a tree, looks longingly down at a happy couple. I’ve always felt a strong connection with it.

“Oh, what must it be to be there,” the vampire is saying.

“Can I see that picture?” I ask Sue.

Sue passes it over.

“You gave me that,” Sue says.

“I did?” I say, surprised. “I want it.”

Christy gets a small bust of Eugene V. Debs, which Sue had put aside for her. She also asks for a quilt in her bedroom.

I want a pair of over-the-top gold, purple and green salt and pepper shakers, which Sue keeps on her dining room table. I also ask if I can keep a striped shirt of Sue’s that I’d borrowed on the fourth day of our visit, when I decided I couldn’t wear the top I’d arrived in a moment more.

I’ll wear it all summer, I think.

***

Photo by Marci Hanners

SUSAN BETH PFEFFER. FEBRUARY 17, 1948 - JUNE 23, 2025

What a beautiful, loving memory of friendship.

Oh my gracious, Joyce. This was unexpectedly so moving for me. I was working as a library associate in Baltimore County when Life As We Knew It came out. I recommended it to everyone of all ages. It’s a masterpiece. I have that whole series and still recommend it to people constantly. I’m so very sad to hear she’s gone because she was an awesome and under-appreciated writer. But I’m so glad she had you for a friend.